Guest bloggers are welcome if you have something to say on one of those themes :-)

To cater for a broader range of reader interests, Mondeto now hosts 3 new blogs, focussed on Children, Global Perspective and Thinking for a Better Future. Guest bloggers are welcome if you have something to say on one of those themes :-)

2 Comments

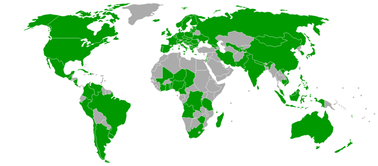

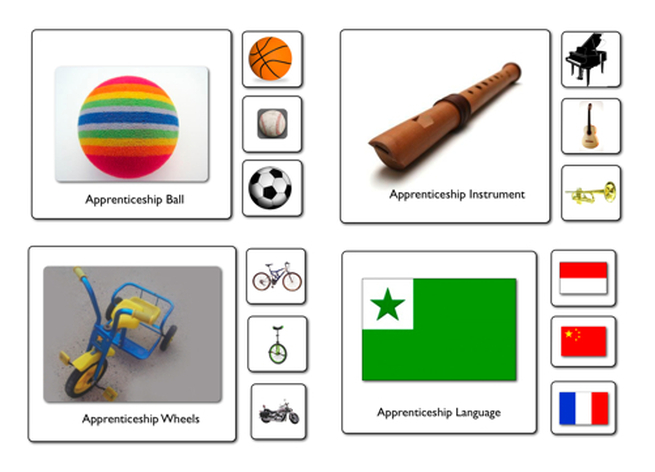

The blog has been pretty quiet for a couple of days while the website has been being overhauled and expanded. The top part of the site still gives quick answers to focused questions about Language Apprenticeship, Esperanto, Mondeto and its products. The new bottom part of the site caters for visitors in less of a hurry who are exploring areas of interest. Under the general headings of Thinking, Global Perspective and Childhood, we are now offering a wide variety of quality links, videos, blogs (including some great guest blogs coming soon) and resources. We hope that you enjoy the new experience and look forward to your comments and suggestions.  I just got my copy of the Spring edition of "Leadership in Focus", a quarterly professional development paper-based journal for Australasian school leaders working in schools from preparatory to year 12 level. Articles in Leadership in Focus centre on issues, trends, debates, reforms, research and developments in primary and secondary education (at the school, district, regional, national, State/Territory and international levels) that impact on schools and the work of practising school leaders. My article, on page 46, goes pretty much like this... In 1996, I was the deputy principal of The Foothills School, an alternative secondary school in Perth, W.A. The school had been teaching Japanese for many years and no-one had ever actually learned Japanese as a result. We held a review to discuss whether that mattered, starting with a brainstorm of our reasons for offering LOTE at all. Our list looked something like this: To engage curiosity and provide a global perspective. To build confidence and self-esteem. To provide the cognitive advantages of bilingualism. To encourage empathy and respect for ESL immigrants. To give our students flexibility to learn other languages as needed later. We also took stock of our resources, especially time. Our students had about 200 minutes a week for 3 years to spend on LOTE, ie less than 400 hours in total. We recognized that most of our goals would not be reached unless students did substantially master the target language. We discovered that motivated adults need 2200 hours to gain basic competence in Japanese, that French or German are available in 600 hours and Esperanto could be learned in just 100 hours. (Our students were far from being “motivated adults”!) Checking back through our goals, we asked (and answered!): Which language would offer the best connection to the global community? Esperanto provides a few million contacts in over a hundred maximally diverse cultures. No other LOTE offers that breadth. Which language would best build confidence and self-esteem, even for students with language deficits? Only Esperanto is designed to be easily learned. It is completely phonetic and uses regular word-building and uncomplicated grammar. No other language can offer as much success, to as many students. Which language best provides the cognitive advantages of bilingualism? In the time available, the students cannot be functionally bilingual in any other language than Esperanto. Which language would let our students know how it feels to be limited in expression by being deprived of one’s mother tongue? Learning another natural language would better demonstrate the difficulty of ESL but, to have the experience of speaking a second language imperfectly, students have to get further into a language than they usually do now, so Esperanto might be the best option here, too. Which language provides most transferable experience for future flexibility? Esperanto uses many Latin and Germanic roots so that there is a lot of transferable linguistic knowledge between English, Esperanto and other European languages. However, in its agglutinative nature and relatively free syntax, it also prepares students well for successful learning of Asian languages. The Apprenticeship Language Effect Studies, in Australia and abroad, have shown that a year of learning Esperanto benefits the learning of Japanese or French even more than an extra year of studying the new target language. The usual explanation is that a year of Esperanto learning is about linguistic structures, not exceptions, so that a holistic image of the essential features of a language becomes visible, instead of being lost in the detail of random idiosyncrasies like silent letters and doubling rules. Having concluded that Esperanto would best set students up for success, in relation to our goals, we decided that lack of a specialist teacher was not enough reason to justify a compromise. If it was worth the students time to learn, it was worth a teacher’s time so I got the job. Before I started teaching, I had 6-7 lessons in Esperanto, I collected resources (mostly old and unacceptable for modern use) and started studying LOTE methodology. In spite of my limited preparation, the course was a great success. By the end of term 1 year 8 were staying in at lunchtime and staying hours late after school to talk to Swiss kids (who had come to school early to talk to us) in Esperanto. They didn’t have a big vocabulary at the time, but they were very keen to use what they had. After 3 years of the program, I transferred to a Montessori primary school which was thoroughly fed up with LOTE. They felt that they had tried everything and found nothing satisfactory. I started teaching Esperanto to my class, then the next one too, and by the end of the year all of the primary school was learning Esperanto as LOTE. As with the high school students, they made good progress and soon reached the stage of being able to communicate, even though the time allowance was barely enough, at 40-60 minutes a week. In the 4th year of the program, 20 of the students travelled to Switzerland to to visit the school I had made friends with years before. The children in the two schools had no common language but Esperanto, and it served the purpose. The last school where I taught Esperanto was a state school in rural NSW, one lesson a week (except for sports days, the first week of term and some other interruptions) to years 5 and 6 for three years. This was not enough for all students to communicate independently in Esperanto. Ten students achieved it before moving on to one of the three local high schools, where they would learn either French, Italian or German. Anecdotal evidence suggests that our students gained significant advantage from their “apprenticeship” language, Esperanto, whichever language followed. The next year, in June 2007, the 8 major Australian Universities held a crisis meeting calling for “creative solutions” to the failure of LOTE (Languages Other Than English) education in Australia. I wondered if what I had been doing for the last decade might be such a solution. Research revealed that the failure of LOTE was nothing new: In 1996, The Australian Languages and Literacy Council concluded that “The key finding of the council's investigation is that our education systems are consistently failing to deliver any worthwhile proficiency in languages.” Further, in 2002, The Executive Summary of the LOTE Report, commissioned by The Federal Department of Education, Science and Training stated that: “Given the questions and concerns that have been raised in relation to LOTE, it is appropriate to ask whether the current model of provision can ever produce better results in terms of language learning, regardless of the amount of funding injected into it.” Primary LOTE education in Australia uses a very different model of provision than other subjects, except music. These two are commonly provided by a visiting specialist, if and when one is available. One disadvantage of this dependence is that a suitable LOTE specialist is frequently not available. For many years there has been a worldwide, "chronic shortage of qualified language teachers, despite measures to encourage recruitment”, as the British Nuffield Inquiry Report noted in 2000. DEST polled school principals to find out why LOTE in Australian primary schools is “consistently failing to produce results”. Where programs have failed, or have been dropped, the explanations offered can be grouped into the overlapping headings of Teacher Availability, Time, Commitment, Continuity and Consideration for the Needs of the Learner. These problems can all be addressed by engaging some lateral thinking: 1. Teachers Australia has no shortage of competent, qualified, primary school teachers who are fully capable of learning anything that we would expect to teach to every primary school child. Could the creative solution, and new model of provision, be something as simple and sensible as using the professional primary educators that we already have? My own experience shows that a generalist teacher can teach a suitable “apprenticeship language” (Lo Bianco, ACER 2010) very effectively, and it may be important that they do so - as language experts frequently cite the problem of Australia’s “monolingual mindset”. This is the idea that it is normal to be monolingual, and that only immigrants seriously speak other languages. Having normal primary school teachers demonstrate willingness and capacity to learn another language to fluency, with the children, is our best hope of changing that mindset. As someone who has been both a classroom teacher and a LOTE specialist, I believe that the primary classroom teacher is the best professional to teach a young child a new language because s/he is the more powerful role-model of non-specialist adulthood and: knows the child’s abilities, maturity and motivations best, has effective techniques for managing the class, is appropriately skilled, qualified and experienced, is with the child all day and can provide extra time or a new task when needed, has the support of colleagues, administration and parents, is already settled in the community (important in rural areas) has control over the classroom environment and timetable, can integrate language use into classroom life and other subjects. Making LOTE education an integrated part of the generalist teacher’s work opens up opportunities for schools to raise standards in other KLA’s through use of other specialists, in science or other subjects, during weekly RFF, or DOTT, time. Not all teachers have the opportunities I had for extensive in-service training, as a LOTE teacher and HOD, so I have spent the last two years preparing the teaching resource I wish I’d had at the outset, “Talking to the Whole Wide World”, which contains both all a teacher needs to know about Esperanto, and a wealth of teaching strategies for use with children of various ages and stages. The book and CD set are no more difficult to use than any other resource normally used by primary teachers. Because rules in Esperanto do not have exceptions, teachers do not have to worry that they will teach something which turns out to be wrong, as would be the case with other languages. In the first year, the class get to share the learning adventure with the teacher, and see that everyone needs to practice, look things up, make mistakes... this is important learning. After the first year, the teacher is probably in the more usual position of being ahead of the class and is increasingly well equipped to provide “language immersion” experiences for the class. These two strategies, “apprenticeship languages” and “language immersion”, are recognized as winners among language teaching methodologies by Prof Joseph Lo Bianco, author of Australia’s language policy (among other things) and other experts. Teacher supply is the reason identified by principals as the main one causing failure of LOTE programs. Fortunately, the solution proposed here also addresses the other four big reasons: Time, Continuity, Commitment and Concern for the Needs of Individual Learners 2. Time Time issues include such aspects as: Total time allowance Starting time Lesson and practice frequency Lesson duration Discontinuity of the program Time on task, and Time flexibility to allow for individual needs. Control of most of these is constrained by dependence on specialists. Well-prepared generalists can optimize these for the character of the particular class, ensuring that language education starts at the right time, in optimally-sized blocks, integrated into the curriculum, by teachers who know their students and are able to allow extra time or extension opportunities to meet the needs of all. The one problem which use of classroom teachers does not, in itself, resolve- is total time allowance. However, if the way that we are employing the generalists is by choosing Esperanto, then that solves the total time problem by offering a language that fits within the current time allowance available to most primary schools for LOTE. 3.Continuity LOTE learning is strongly cumulative, so continuity is essential. Primary Esperanto education can provide continuity by reducing dependence on scarce specialists (who may leave) as well as by developing cumulative communicative competence in a single language whilst generating interest in, and understanding of, the widest variety of cultures. Because students can reasonably expect to master Esperanto in the primary school, choosing a third language in secondary school is less anticlimactic than abandoning a partly-mastered language to start again. Whichever language(s) they choose to study later, mastery of Esperanto as a first foreign language makes the next one easier and quicker. 4. Commitment The Primary Esperanto Strategy is fair, effective and practical enough to inspire the commitment of principals, teachers, students, parents and the wider community. 5, Sensitivity to the Needs of Learners Best educational practice requires consideration of the characteristics of the learners, both as a group and as individuals. Primary Esperanto is a strong strategy for the development of empathy, cognition, perspective, literacy, self-confidence and linguistic potential. It also provides maximum responsiveness to the needs of individual students by putting the LOTE program into the hands of the classroom teacher who cares for each child and knows them best. To conclude, Esperanto may be the best choice for your primary school LOTE strategy because: To do so models fairness, and equal respect for all cultures. Its grammatic regularity and phonetic nature make it accessible in the time available. Educationally disadvantaged students often gain confidence from spelling and reading success in Esperanto, even if it has been elusive in English. Esperanto promotes English literacy, and later language learning, through transparent grammatical structure, sound/symbol constancy and use of Latin roots. It promotes numeracy by the exact match of words and concepts to the base ten number system and other primary mathematical concepts such as fractions and multiplication. Esperanto encourages creativity, analysis and synthesis through extensive use of regular wordbuilding. Esperanto gives access to the widest variety of cultures in all dimensions: language, religion, arts, environment, politics, economy, resources and intercultural relationships. This broad perspective provides context for a variety of future studies. Esperanto has no exceptions to its “rules” so students have time to learn more transferable general LOTE concepts, skills and attitudes which greatly facilitate learning other languages later. Esperanto allows quality preparation for generalist teachers in an affordable time frame. Classroom teachers who teach Esperanto model life-long learning and the value they put on languages. Classroom teachers already have the full support of colleagues, administration and communities to make language learning as an integral part of school culture. Primary school graduates, with experience of successful language learning, are best-prepared to make a meaningful commitment to the study of any third language and its culture in secondary school and beyond.  All I'm saying is simply this, that all life is interrelated, that somehow we're caught in an inescapable network of mutuality tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly affects all indirectly. For some strange reason, I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be. You can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be. This is the interrelated structure of reality. — Dr. Martin Luther King Jr Our children will be the best version of themselves when they can meet other global citzens on equal terms and let them be their best too.  Deborah Fallows, linguist and author of Dreaming in Chinese: Mandarin Lessons in Life, Love and Language, discusses the recent history and unique features of the Chinese language. Click on the podcast button to listen.  This is an interesting story in a lot of respects, but one angle that appealed to me is the idea that the dichotomies of ancient vs new, and natural vs designed, are not nearly as clear-cut as they might seem. Deborah Fallows explains that not only is Mandarin "new" to the majority of Chinese people, whose families never knew it until a century ago, but that much of Mandarin itself, including simplified Chinese and pinyin, is deliberately designed and considerably younger than even that. The power of the Chinese government to make changes and insist on their adoption is probably unrivalled in the modern world. Will it extend even beyond China's boundaries? If you fancy an Esperanto to Mandarin adventure of your own, you might like to consider starting at the Chinese Island of Hai Nan Dao (sometimes written Hainan Dao), which means "South Sea Island". The island is about half the size of Tasmania and was traditionally used as a place to exile people. Now they've noticed that it is a lovely place to be in the Chinese winter- being on the same latitude as the Phillipines, and are promoting its use for tourism.  Every January-February, the Baza Esperanto Kursaro is held at the University of Hainan and turns raw beginners into capable speakers in that time. In 2012, this will be joined by a new "Esperanto University" in which professors from around the world, including China of course, will deliver short courses in their own specialties, in Esperanto. It all makes for a dramatically different summer holiday and very affordable- the entire month of food, accommodation and instruction costs only $600 per participant- it'll cost you that much to stay home :-) Click the picture to visit the website.  Anatoly Karlin writes a great little piece on his early experience with Esperanto. He's obviously done his homework because he gets quite a bit of the big picture too. His story starts: " In the course of myChinese adventures, all other languages started to seem a lot easier. So needless to say that Esperanto, one of the easiest of them all, looks like just a walk in the park now. In particular, I’m interested in what the glossophiles here think about it, i.e. yalensis and Lazy Glossophiliac. Here are my rambling thoughts on it: * It is easy. VERY easy. I have been studying it for three days, and I can already say many phrases: e.g. the one in the title (“Esperanto is the easiest language in the world”). Its vocabulary is about 60% Latinic, 30% Anglic-Germanic and 10% Slavic; its grammar is simplified Latinic; its morphology and semantics are largely Slavonic. Being a natural language, everything is very logical, it is entirely phonetic and there are no exceptions. Root words can be easily transformed from verbs (add in “i) to adjectives (add an “e), an adjective (add an “a), a place where it is done (add “ej”), a professional who does it (add “ist”), a female version (add “ino”), a diminished version (add “et”), a magnified version (add “eg”), etc. For people with some familiarity with European languages, the vocabulary is a piece of cake. It will be a lot tougher for Asians, but nonetheless even for them it will still be an order of magnitude easier than starting from a natural language. * Despite its easiness, I’m discovering Esperanto is very flexible. In a sense, even more so than languages like English or Chinese, which are largely bound by the Subject-Verb-Object structure. Though I may change my mind as I get more advanced, so far it seems to me to be as flexible as Russian, which is amazing considering its grammar is orders of magnitude simpler. Quite frankly, of the languages I’ve looked at it in any detail, it is my favorite by far (the full rankings: Esperanto; Spanish; Russian; Latin; Chinese; English; French; German). * Why learn it? First, there are studies showing that students who spent a year learning Esperanto were able to assimilate French and other languages quicker thereafter, eventually overtaking the control groups that didn’t study Esperanto. Only about one year max is needed for Esperanto fluency. But there are accounts of some people accomplishing it in days. There are monthly meetings of Esperantists in the Bay Area. I’m planning to attend the next one, and I already feel I won’t be embarrassed to open my mouth. By then I will probably be far better at it than at Chinese, which I’m studying for the fourth month now; a depressing thought, that. This brings us to the second reason why Esperanto is awesome .........(You can read the rest here.)  The week has been pretty much blogless because I've been out and about for conferences. I spoke at the ACEL conference in Adelaide on Wednesday and  the Free Linguistics Conference in Sydney on Sunday. Both talks were about how Apprenticeship Language Learning using Esperanto is a useful strategy for sustainable change, in giving children a first fluent foreign language, a broad and changeable intercultural perspective and the skills and motivation for other language success. The presentation at the Free Linguistics conference went on to give an insight into two of the first schools to have adopted the strategy using the "Talking to the Whole Wide World" resource, since it was published in April 2010. These are Sutherland Montessori in Sydney and Jakarta Montessori School. They are both using the resource as it was designed to be used- to teach the teachers and students together- and both are making good progress. They intend to start using their Esperanto to communicate with each other in early 2012, and perhaps with other schools, in other countries, later in the year. One question from the ACEL group was about the distribution of Esperanto around the world- where is it most used?  I had already shown this map of countries with enough speakers to warrant a national Esperanto association (coloured green). As he supposed, the density of Esperanto speakers in the green countries varies. We see more Esperanto speakers in South Korea, Germany, Switzerland, Brazil , Vietnam and French-speaking African countries, places where there is more than one good contender for the role of second language. Although Australia is certainly not yet among the countries most eagerly embracing Esperanto ( we don't yet eagerly embrace any other languages), we are in this same position where there is no really compelling case for any particular language to be the one for all of us, so we may join the hotspots list when we realize that bilingualism is both valuable and affordable! If you have any questions, I'd be happy to answer comments :-)  According to ACARA, responsible for developing Australia's national curriculum: The most direct means for learning about and engaging with Indigenous communities and Asian countries and people is to learn their languages. This constitutes fuzzy thinking because it confuses an effect at National level with an effect at the level of each individual child for whom we are responsible. How are our students realistically going to learn “their languages”? We almost never succeed in teaching students even one foreign language well enough to exchange genuine cultural insights. Although it is traditional to act as if 100 students having insight into 1 foreign culture each, is the same thing as 100 students knowing something about 100 (or even 10) foreign cultures, it isn’t: Understanding Japan is not understanding Asia. Asian cultures have a vast diversity of languages, religions, economic and political systems, artforms and other priorities. Even if our current system worked perfectly, which of course it doesn’t, we would still be educating bicultural graduates, not multicultural ones and that is a bar too low for the education of global citizens. Indigenous and Asian cultures are diverse and important, and the plurals are important. Putting plurals on the goals and then delivering singles at implementation does nothing to increase the trust with which Australians view academic advice. To achieve the cross-curiculum priorities for individual Australians we need pathways such as ALL to keep our delivery general at the F-6 stage, so that children really do get to combine consistent cumulative language learning with a broad and shifting intercultural perspective, responsive to student interests. This slideshow introduces some of the classes of primary children who are currently learning Esperanto and are available to bring some personal significance to parts of the globe that would otherwise be beyond reach.  Some fundamental linguistic concepts and skills which can be taught using Esperanto as an apprenticeship language include:

Any language can be used to teach these transferable concepts but, where time is limited, languages with a similar alphabet to English, phonetic spelling and more regular grammar will get further through the list than those without these features. Literacy skills, problem solving skills and thinking skills are developed in learning any language. However, students learning Esperanto spend more time practicing higher order thinking skills, such as application of understandings to creative tasks, synthesis and analysis of texts and evaluation processes. This is because less time is needed for recognition and recall in Esperanto, because it lacks the idiosyncratic variations in spelling, grammar and pronunciation found in most national languages. Wisdom has been defined as perceptiveness to patterns. Pattern use in Esperanto is extensive and consistent, which makes pattern recognition intrinsically rewarding and a source of competence. The effect of several years of such encouragement at an impressionable time invites further investigation. Of course, the intrinsic motivation for language learning is language use, so we'll look at the third reason for welcoming Esperanto into your school - who your students will have to talk to, next time. |

AuthorPenny Vos Archives

July 2016

Categories

All

015

|